Copyright ©2023. All rights reserved by the author.

Figure 1. Alice Boughton, Albert Pinkham Ryder. 1905. Photograph. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Public Domain. |

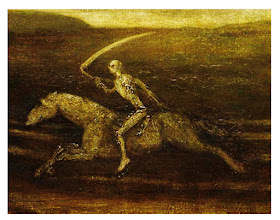

Figure 2. Albert Pinkham Ryder, Death on a Pale Horse (The Race Track), ca. 1896–1908. Oil on canvas; 28 x 35 in. The Cleveland Museum of Art. Public Domain. |

The Artist

Albert Pinkham Ryder descended from the early English settlers of the Plymouth Colony on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. During the 1630s, one of his ancestors left the colony to help found the town of Yarmouth, and by the mid-nineteenth century, the family had settled further inland to New Bedford, Massachusetts. This was where the future artist was born, on March 19, 1847, the youngest of four brothers. During the nineteenth century, the Ryder family was caught up in the revivalist spirit of the Protestant Great Awakenings, and they joined the American Methodist movement. The English clergymen John Wesley, his brother Charles Wesley, and George Whitefield helped establish the Methodist Revival in the southern colony of Georgia during the 1730s, which quickly spread up the Eastern Seaboard in the next decade, reaching New York, Boston, and all the principal cities and towns of New England by the mid-1740s (see Carwardine 1972). Albert’s grandparents and his parents, Alexander and Elizabeth (Cobb) Ryder, were devout Methodists. His grandmother, mother, and other women in his family even dressed in the “plain manner” more commonly associated with the Quakers and Amish (Sherman 1920, 12). The artist’s strict religious upbringing shaped his worldview and the subjects he chose to depict.

Each of Albert Pinkham Ryder’s older brothers served in the military during the Civil War, and after the war was over, each brother relocated to New York City in search of economic opportunities. Albert and his parents soon followed, and by 1871 the whole family was reunited and living together again in Manhattan in a small house on West Thirty-fifth Street (Broun 1989, 18, 182). The artist’s father, Alexander Ryder, helped support the family by working in a variety of trades and even served as a church sexton in a local Methodist congregation.

Albert Pinkham Ryder showed an artistic aptitude at an early age, and as soon as he arrived in New York, he began taking instruction in drawing from William Edgar Marshall (1837-1906). Marshall’s fame was based primarily on his engraved portraits of Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant, and he accepted many students into his studio. After Ryder honed his skills for several months, he applied to The National Academy of Design and was accepted. For the following four years, Ryder took part in drawing courses at the Academy’s building on Park Avenue and Twenty-third Street, sketching plaster casts of famous ancient sculptures and producing studies of live models. Around the same time, he took his first trip to Europe but stayed only one month. He would return to Europe only twice, in 1887 and 1896, but both times he again quickly returned.

Art historians and curators often mischaracterize Albert Pinkham Ryder as either somewhat naïve or as a wholly unique artist. This may be because as Ryder aged, he became more and more reclusive, living and working in seclusion, and his visual idiom grew more eccentric and visionary. In this progression, Ryder was similar to the innovative post-Impressionist Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), Ryder’s near contemporary. Van Gogh has also been misunderstood as a mere oddity or as an outsider to the art world who preferred only to pursue his own muse and disregarded the work of others (see Bailey 2019). But, in fact, both van Gogh and Ryder were well acquainted with the history of European painting, and both were particularly impressed by the landscapes and genre scenes of the French Barbizon School (Homer 1961, 283; regarding Ryder’s other influences, see Evans 1986). Ryder was known to frequent The Metropolitan Museum of Art and leading galleries to see the paintings of Jean-François Millet (1814-1875), bucolic scenes infused with spiritual messages. Ryder also borrowed from the softly generalized forms, rough brushwork, and “dusky golden tonalities” of the Barbizon painter Théodore Rousseau (1812-1876) (Homer 1961, 283). However, while Ryder was a sophisticated art student, like van Gogh, he had an unusual disposition.

An Odd Personality

During the twelve years that Albert Pinkham Ryder worked on Death on a Pale Horse (The Race Track), he lived in a “row house” at 308 West Fifteenth Street, near Eighth Avenue, specifically in a cramped attic studio on the second floor at the rear of the building (Taylor 1984, 3). One of Ryder’s few close friends during this period was Charles Fitzpatrick, who lived at the adjacent row house. Fitzpatrick described 308 West Fifteenth Street as “an old-fashioned house … one of those peculiar houses that attract professional people of small means, most of the tenants [were] artists, sculptors, musicians, doctors, and newspaper men” (Fitzpatrick 1984, 8).

Ryder took no interest in the condition of his tiny studio apartment. Fitzpatrick recalled the artist’s room was cluttered with “bags and barrels filled with paper, empty food boxes, ashes, old clothes, especially under-garments … all soiled and in a fearful condition, mice that had decayed in traps, food in pots that had been laid aside and covered with paper and forgotten” (Fitzpatrick 1984, 8). Ryder often appeared in public in a similar state of disrepair, his clothes disheveled and his rugged beard untrimmed. More than once, the city housing authority was called out to investigate the deplorable state of Ryder’s dwelling. When they did, the artist was found “sleeping on a rough cot” or puttering around in his overalls “with a pair of old leather slippers on his stockingless feet.” Outsiders might have viewed his studio as “the abode of dirt and disorder,” but Ryder himself, “the poet and dreamer, had a very different idea. ‘I have two windows [he explained, which] look out onto an old garden, [and] I would not exchange these two windows for a palace with less a vision than this garden with its whispering leafage – [it’s] nature’s gift to the least of her little ones’” (Sherman 1920, 19-20).

Ryder placed a far higher value on his independence and individuality and his drive to document his intense inner imaginings than on material comforts. In a letter dated 1900, he wrote, “It is the first vision that counts. The artist has to remain true to his dream, and it will possess his work in such a manner that it will resemble the work of no other man – for no two visions are alike. Those who reach the heights have all toiled up the steep mountains by a different route. To each has been revealed a different panorama” (Homer and Goodrich 1989, 205).

Completing a painting was rarely the artist’s primary goal; rather, working through an initial conception was his fascination. The abstract idea underlying a work meant more than its fulfillment (Soby and Miller, 35). Ryder was notorious for his frustratingly slow process and his “tortoise-like pace.” He labored over and over for as long as fifteen years on a single painting, developing a “neurotic attachment” that prevented patrons from taking works from his studio (Homer 1990, 86). The artist’s obsessivity was exacerbated by his poor eyesight, brought on by a childhood infection, which made prolonged visual concentration extremely difficult. In addition, Ryder suffered from various other ailments, including gout, kidney disease, insomnia, and a nervous disorder (perhaps “neurasthenia”), that impeded his progress (Ross 2003, 89-90). As a result, in a career lasting fifty years, Ryder’s entire oeuvre numbered just over one-hundred-fifty paintings.

A Spiritual Muse

Albert Pinkham Ryder undoubtedly had an eccentric personality and was withdrawn, but he was not simply unsociable. Ryder disregarded the state of his apartment and avoided the company of others largely because of an obsessive preoccupation with his work. As Ryder aged and became well-known, though, he attracted the attention of a younger generation of painters living and studying in New York. One of these younger painters was the prominent social realist Philip Evergood (1901-1973). Evergood’s parents were close acquaintances of Ryder’s next-door neighbors, Charles and Louise Fitzpatrick, and over time, Louise and Flora Evergood (Philip’s mother) became the best of friends.

As a child, Philip Evergood often visited Ryder’s studio and “played among [his] canvases” with Fitzpatrick’s adopted daughter Mary (Taylor 1984, 2). Evergood expressed admiration for Ryder’s personal magnetism: “He drifted smoothly along, taking everybody, children, women, trees and sky as a matter of course. He would talk to strangers as though he had known them all his life, though he only had a few real friends (Evergood 1984, 6). On warm summer evenings, Ryder often accompanied Louise and Mary Fitzpatrick to church, preferring to sit outside “on the church steps waiting for them to come out” (Taylor 1984, 4). The church doors were kept open during the summer, and Ryder sat listening as Mary sang in the choir and at times, performed a solo (Fitzpatrick 1984, 13).

The Fitzpatricks outlived Flora Evergood (and Albert Pinkham Ryder) by many years, but they continued their relationship with Philip Evergood until their own deaths. Charles Fitzpatrick often spoke with Philip Evergood about his artwork, but as Charles aged, his attitude changed. As he neared his own death, he grew more and more religious. Evergood was surprised when Fitzpatrick began voicing “gruffy disapproval of [his] work just before he died [in 1932]. He acted as though my paintings were obscene. … I was painting all imaginative compositions with nudes, and [Charles] used to preach to me to change my ways and to think of Ryder’s religious fervor [emphasis added]” (Evergood 1984, 5). Louise Fitzpatrick made similar suggestions. She encouraged Philip to go study Ryder’s pictures closely whenever he could, not to see the way he painted, but to “feel the mystic spirit of his soul” (Evergood 1984, 5). It seemed to Philip Evergood that Louise gradually transformed into “a kind of Saint whose fervor and love for humanity was completely tied up in her fervor and love of the master. She would speak of Ryder and Christ in the same breath” (Evergood 1984, 7). Because of Albert Pinkham Ryder’s reliance on (often religious) inspiration, and his prioritizing of subjectivity and individuality, he is often considered a latter-day Romantic.

Romanticism was a wide-ranging artistic and cultural movement that swept across Europe in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. European Romantics shared a nostalgia for the past and were “interested in the mind as the site of mysterious and unexplained” phenomena (Adams 2002, 754). Chief European Romantics such as William Blake (1757-1827) and Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) painted with a rich and religious imagination (see Polistena 2009). Romanticism arrived rather late in the United States, though, and American Romantics, such as many of the Hudson River School, often worked in isolation as bohemian artists (Kuspit 1963, 219).

Most art historians agree Albert Pinkham Ryder was a Romantic, and many debate whether he also deserves the epithet “mystic” since he opted for a humble life of contemplation in order to attain a spiritual apprehension that lay beyond the intellect or human perception. Historian and psychoanalytical art critic Donald Kuspit dismissed this epithet, preferring to see Ryder’s “hyperbole of moodiness and passion” as characteristic of his unique “conception of expressiveness” (Kuspit 1963, 219). On the other hand, Columbia University Professor of Art Barbara Novak believed Ryder’s “entire oeuvre, religious or secular [was] an act of devotion”; he saw “all of nature within the purview of the Almighty” (Novak 1969; quoted in Dillenberger and Taylor 1972, 154). Lloyd Goodrich, the longtime Director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, concurred, calling Ryder “one of the few authentic religious painters of his period – in whom religion was not mere conformity, but deep personal emotion. The life of Christ moved him to some of his most tender and impressive works” (Goodrich, 1959; also quoted in Dillenberger and Taylor 1972, 154).

The work that will now be examined, Death on a Pale Horse (The Race Track), offers a fascinating balance of Ryder’s competing passions, 1. his desire to visually realize his initial inspiration or conception, and 2. his desire to reach “beyond the place on which [he had] a footing,” to express a transcendent, spiritual concept.

The Inspiration

Albert Pinkham Ryder’s personality could scarcely have been more distinct from that of his older brother, William Davis Ryder (1837-1898) (Hotel Albert 2011). William was far more pragmatic and business-oriented. After serving in the Union Army during the Civil War, William came to New York City and opened a large and successful restaurant at Broadway and Howard Street. He then invested his earnings in the hotel business and became the manager of the Hotel Albert, located at 32 East Eleventh Street (fig. 3). On occasion, Albert stopped into the establishment to visit his brother and to take meals (fig. 4). On one of these occasions, he received his initial stimulus for Death on a Pale Horse (The Race Track), which he later recounted in detail:

“As to how I came to paint ‘The Race Track’ – it was rather an inspirational matter. At this time my brother was the proprietor of the Hotel Albert and I frequently used to get my meals there and got acquainted with many of the waiters. I got acquainted with one, but I cannot recall his name, who was unusually intelligent and a proficient waiter and I sometimes used to chat with him. This was about the time the Dwyer brothers had their phenomenal success with their stable of race horses, as they won about all the important events throughout the country for over three or four years. In one of my talks with this waiter he mentioned this fact and that this was an easy way to make money. I, of course, told him that I did not consider it so, as there was always ‘many a slip between the cup and the lip,’ and advised him to be careful. Not long after this, in the month of May, the Brooklyn Handicap was run, and the Dwyer brothers had entered their celebrated horse, Hanover, to win the race. The day before the race I dropped into my brother’s hotel and had a little chat with this waiter, and he told me that he had saved up $500 [equivalent to around $15,000 today] and that he had placed every penny of it on Hanover winning this race. The next day the race was run, and as racegoers will probably remember, Hanover came in third. I was immediately reminded that my friend the waiter had lost all his money. That dwelt on my mind, as for some reason it impressed me very much, so much so that I went around to my brother’s hotel for breakfast the next morning, and was shocked to find my waiter friend had shot himself the evening before. This fact formed a cloud over my mind that I could not throw off, and ‘The Race Track’ is the result” (Sherman 1920, 46-48).

Figure 3. Hotel Albert, ca. 1907. | Figure 4. Hotel Albert dining room, ca. 1907. |

Figure 5. Hanover, ca. 1887. | Figure 6. Monmouth Park, Eatontown, NJ, 1880. |

The Dwyer Brothers Stable was a successful thoroughbred racing team owned and operated by the brothers Philip Dwyer (1844-1917) and Michael Dwyer (1847-1906) (see Barnes and Wright 2018). The Dwyer brothers earned their fortunes in the Brooklyn meat packing industry and then founded their extremely successful horse racing operation in 1876. Over the next fifteen years, Dwyer horses won five Travers Stakes, five Belmont Stakes, two Kentucky Derbies, and a Preakness Stakes. They maintained a stable that included several U.S. Champions, but their most famous racer was Hanover, the American “Horse of the Year” in 1887 (fig. 5).

Hanover won his first seventeen races, his greatest triumph coming at the Belmont Stakes, held in June 1887 at the Jerome Park Racetrack in The Bronx. He won the Belmont by an amazing 15 lengths. Because of this great victory, Hanover was an overwhelming favorite to win the inaugural Brooklyn Derby (or “Brooklyn Handicap”), held in July 1887 at the (now-defunct) Gravesend Race Track near the Coney Island amusement parks. And, in spite of Ryder’s apparently foggy recollection quoted above, Hanover did, in fact, win the Brooklyn Handicap in 1887. It was an incredible year for the steed, a year in which Hanover started twenty-seven races, won twenty times, finished second five times, finished third only once, and finished completely “out of the money” also only once (National Museum of Racing 2023). The only time Hanover finished worse than third in 1887 was at the Omnibus Stakes, held in late July at Monmouth Park in Eatontown, New Jersey (American Classic Pedigrees 2023) (fig. 6).

A bettor who makes a “win wager” receives a large “payout” if their chosen horse wins the race. Since this is a risky bet, it has a high payout. A bettor who makes a “place wager” receives a payout if their chosen horse finishes either first or second. A bettor who makes a “show wager” receives a payout if their chosen horse comes in either first, second, or third. Hanover’s remarkable winning percentage in 1887 (74%) led Ryder’s waiter friend to believe the horse was basically a “sure thing” to win, so he placed a very chancy “win wager” on Hanover, apparently, at the Omnibus Stakes. And when Hanover came in third, he, unfortunately, received no payout whatsoever. A safer show wager would have resulted in at least a small payout, and presumably, Ryder’s friend would not have taken his own life.

The Concept

Like many Romantic painters, Albert Pinkham Ryder was stimulated by famous literary sources, from Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales (see Constance, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), to Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” (see With Sloping Mast and Dipping Prow, Smithsonian American Art Museum), to the vivid texts of the Bible (Homer 1961, 280). Exhibitions often juxtapose Ryder’s paintings with explanatory labels quoting such texts, shining a light on his work’s deepest meanings. Unlike some other Romantic artists, though, Ryder did not merely illustrate literary sources; rather, he created “pictorial dramas” encouraged by transcendent themes, translating them into something purely visual and “purely individual” (Goodrich 1949). This holds true for Death on a Pale Horse.

Ryder suggested the suicide of his waiter friend motivated him to paint Death on a Pale Horse. However, the suicide occurred in 1888, and he did not begin his painting until eight years later (ca. 1896); he then labored over it for another dozen more years (until 1908). This is a prime example of his “tortoise-like pace.” Significantly, when Ryder worked on the painting, his closest family members died in succession: his mother in 1893; his brother William in 1898; and, finally, in 1900, his father passed away following a long illness. In these years, it may have seemed to the artist that, sadly, death was continually galloping through his life. In 1928, the director of the Cleveland Museum of Art, William Milliken, proposed that in the Cleveland painting, Ryder “deals with the eternal problem of death, not in any mood of morbid curiosity, but instead with an inevitability,” which is characteristic of the subject matter itself (Milliken 1928, 65).

Ryder believed he suffered from a nervous condition, what today we would call an anxiety disorder, and this condition was undoubtedly exacerbated by losing his dearest family members. After his mother died, he sought support from one of his patrons, a therapist named Dr. Albert T. Sanden. Between 1895 and 1915, Dr. Sanden treated the artist at his New York City apartment and at Sanden’s upstate country home and dairy farm in Goshen, New York (Ross 2003, 86). The two men eventually became good friends and continued an active correspondence until shortly before the artist’s death. In 1907, Ryder wrote to Sanden, “There is no one in the world I feel more comfortable with than [yourself]” (Ross 2003, 91-92). At the same time Ryder was receiving treatment for his nervousness, he apparently also sought solace by reading Bible passages, specifically the sixth chapter of the book of Revelation, which is also known as “The Apocalypse.”

The Apocalypse contains some of the Bible’s most awe-inspiring figurative prose, and none of its passages is more memorable than the account of “The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse,” who, the text says, will be sent to deal with humanity on God’s behalf at the end of the ages. The author of the Apocalypse revealed this vision:“I heard, as it were the noise of thunder, [and] one of the four beasts saying, ‘Come and see.’ And I saw, and behold a white horse: and he that sat on him had a bow; and a crown was given unto him: and he went forth conquering, and to conquer. And … I heard the second beast say, ‘Come and see.’ And there went out another horse that was red: and power was given to him that sat thereon to take peace from the earth, and that they should kill one another: and there was given unto him a great sword. And … I heard the third beast say, ‘Come and see.’ And I beheld, and lo a black horse; and he that sat on him had a pair of balances in his hand. And I heard a voice in the midst of the four beasts say, ‘A measure of wheat for a penny, and three measures of barley for a penny; and see thou hurt not the oil and the wine.’ And … I heard the voice of the fourth beast say, ‘Come and see.’ And I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that sat on him was Death, and Hell followed with him [emphasis added]. And power was given unto them over the fourth part of the earth, to kill with sword, and with hunger, and with death, and with the beasts of the earth” (Revelation 6:1-8 KJV).

Many Romantic artists attempted to envisage and portray the highly symbolic passage, but few, if any, equaled the original text’s blend of simplistic language and fantastic description, nor its palpable sense of sublime terror (see Considine 1944). The Anglo-Irish philosopher Edmund Burke (1729-1797), who anticipated the Romantic movement, defined “the sublime” as an artistic effect that produces the strongest emotions; whatever “operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime” (Burke 1757, 58). Perhaps the two visual artists who most closely captured the terror of the Apocalypse’s text were the German Renaissance painter and printmaker Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) and Albert Pinkham Ryder.

In Dürer’s woodcut print entitled “The Four Horsemen,” of 1498, he attempted to hold faithfully to the biblical text (fig. 7). Dürer’s first three riders go forth with power, spreading war, plagues, and famine. Below is the fourth rider, Death, a withered old man with a long white beard, hollow eyes, and a gaping mouth (fig. 8). The emaciated rider sits atop a similarly emaciated horse with a pitifully exposed ribcage, who tramples indiscriminately over humanity. Death wields a trident, which he employs to fling bodies into the jaws of a ravenous Hellmouth. His unfortunate victims include a shrieking peasant, a common housewife, a dandified merchant, a horrified burgher, and a tonsured priest. The gruesome harvest includes the poor and the rich, the mighty and the humble (see related biblical passages Ecclesiastes 9:5; Hebrews 9:27). Dürer borrowed from the medieval literary and pictorial allegory known as the Dance of Death or Danse Macabre, in which Death was symbolized as a dancing skeleton who merrily leads a cross-section of society toward the grave (see Eisler, 1948) (fig. 10).

Albert Pinkham Ryder departed from Renaissance (and medieval) iconographic conventions by separating the figure of Death from the other horsemen, which suggests Ryder’s true intention. His image is more a meditation on a theme than an illustration of a biblical text. Ryder also placed Death at the center of his composition, and, instead of representing an aged and ailing man, Ryder’s Death more closely resembles the skeleton of a Danse Macabre or illustrations of the personification of death known as “the Grim Reaper” (figs. 9-11). To underscore the latter association, the artist took away Death’s traditional trident (fig. 8) and gave him the Grim Reaper’s preferred harvesting tool, a scythe (fig. 11).

Figure 9. Detail of fig. 2. | |

Figure 10. Swiss engraving of Death Dancing with a Cook. Public Domain. Figure 11. French illustration of the Grim Reaper. Public Domain. | |

From the Middle Ages onward, European and American artists almost invariably presented the Death figure of the biblical Apocalypse as still living, though just barely. He will bring death to humanity but is not quite dead himself. The only major exception to this convention predating Ryder’s image was a drawing by the English painter John Hamilton Mortimer (1740-1779). Mortimer’s drawing has been lost but is nonetheless known by an etched copy circulated by another artist in 1775 (fig. 12). One art historian described Mortimer’s scene as a “horrible imagining,” a prime example of a “conspicuous current of ‘Gothic’ terror which first emerged in British art in the 1770’s” (Ziff 1970, 529). Ryder seems to have been aware of the widely-circulated etching. As Ryder would do a century later, Mortimer conceived of Death as an isolated skeletal horseman. Mortimer also used a dark, threatening sky as a foreboding backdrop to intensify his drama. Ryder’s setting is similar. William Milliken saw echoes of Ryder’s ghostly horseman in the “livid clouds” and “weird patches of deep blue” of his ghostly sky (Milliken 1928, 71). Mortimer’s disturbing drawing inspired later artists of various inclinations, including Benjamin West, William Blake, and the poet Charles Baudelaire (Ziff 1970, 532), and perhaps now, Albert Pinkham Ryder should be added to this illustrious list.

Ryder made other interesting iconographic choices. The author of the biblical Apocalypse wrote, “I looked, and behold a pale horse: and the name that sat on him was Death, and Hell followed with him” (Revelation 6:8). Although ostensibly, Ryder distilled this passage to its absolute essentials, he did not forget to include Hell. The biblical term transliterated as “Hell” or “Hades” from an original Greek term (ᾅδης) is an equivalent of the Hebrew term Sheol(שְׁאוֹל), the dark realm of the dead inhabited by disembodied spirits. The Hell accompanying Death on a Pale Horse is often represented as a mysterious, quasi-mythological beast, such as Dürer’s Hellmouth or Mortimer’s dragon-like creature (figs. 8, 12). Ryder decided on a snake, specifically a hooded cobra, a species that is not indigenous to North America but ranges widely across Asia and Africa (fig. 13). It seems, though, that Ryder did not intend to associate Hell with a place but to associate Hell with evil or temptation, particularly with the uncontrolled desire for money, or greed. To make this connection, it is necessary to go back and reconsider how the artist described his initial inspiration.

Ryder said when he was speaking with his ill-fated friend at the Albert Hotel, the waiter brought up the racehorse Hanover’s impressive record and his belief that betting on the horse offered “an easy way to make money.” Ryder gave an intriguing response: “I, of course, told him that I did not consider it so, as there was always ‘many a slip between the cup and the lip’ [emphasis added], and advised him to be careful.” The artist referenced an ancient proverb originally attributed to the third century B.C. Greek poet Lycophron, but often repeated in European and English literature, including in Charles Dickens’s last completed novel, Our Mutual Friend (see Hecimovich 1995). The proverb’s perceived truth is that even though a prospect may appear very promising, a person should not be overconfident about future success. A related idiomatic expression is “Don’t count your chickens before they hatch.”

Albert Pinkham Ryder was a spiritually minded person, and he may have found his inspiration from a similar biblical passage: “Man proposes, but God disposes” (Proverbs 19:21 TLB). Ryder advised his friend to recognize the role of uncontrollable destiny in his life and to not be unduly tempted by the lure of easy money. The snake Ryder included in his painting brings to mind the biblical book of Genesis, which describes how a “serpent” (or “snake” [נָחַשׁ]) tempted Adam and Eve to eat forbidden fruit growing in the garden of Eden and that as a result of giving into their temptations, they died (Genesis 3:1-19). Perhaps Ryder saw parallels in his friend’s story. He succumbed to the lure of temptation and, as a result, was gathered up by Death on a Pale Horse.

Another element that merits attention in Ryder’s painting and is an element that is easily overlooked but is still ripe with symbolic meaning: namely, the way the artist attended to movement. Surprisingly, Ryder makes the pale horse his most active element. The author of the Apocalypse used the Greek term chlōros (χλωρός) to describe the horse’s color. The term does not denote simply a paleness but specifically signifies the insipid yellowish-green tint that characterizes cadavers and other decaying life forms (see Mark 6:39). Like his deathly rider, the horse is beginning to rot and putrefy and turn yellowish-green. Although Ryder painted his horse with this sickening hue (fig. 9), he also flouted expectations by depicting a surprisingly healthy and active animal. Indeed, Ryder’s horse more closely resembles Hanover than Dürer’s sickly steed (figs. 5, 8).

In the sinister contest Ryder portrays, Death and his speedy mount are the sole competitors; at the end of this race, the race of life, the “phantom rider,” and his “phantom horse” will inevitably win (Milliken 1928, 71). The horse gallops at a furious pace without caution. The Cleveland Museum of Art’s conservation department conducted an x-ray analysis of Ryder’s painting, which revealed the artist originally placed the animal’s hoofs under its body in the natural pose of a running horse, but later decided to splay the legs unnaturally (see Muybridge 1979, xv-xix). He apparently did this to emphasize the horse’s speed (Cole, 2023). There is another peculiarity: Ryder’s horse races clockwise around the track. This goes against the norm in the United States, where horses traditionally race counterclockwise. The Cleveland Museum of Art’s American Paintings Curator has speculated that Ryder intended to convey the message that in the natural progression of each person’s life, death is always riding toward us in the opposite direction, and as time passes, the distance between us and our demise gets smaller and smaller (Cole 2023).

The message that death is inevitable is underscored by the last remaining iconographic feature: the rotting tree on the right side of Ryder’s composition (fig. 14). The remains of the tree are fixed and stationary, in contrast to the racing horse but bloom with symbolism. Ryder was arguably America’s last great Romantic landscape artist, and his art was partly indebted to New York State’s Hudson River School, a group of Romantic landscape painters known for infusing nature with allegorical spirituality (Kelly 1989, 174). For example, the Hudson River School painter Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900) often used a tree that had been blasted and destroyed by lightening as “a substitute for a human being [and] as a potent metaphor for the endless cycle of life and death” (Ellis 2019, 4) (fig. 15). If Ryder intended to portray Death and his pale horse setting off at the beginning of their race, then it was surely no accident that he placed a lifeless tree at their finish line.

Figure 14. Detail of fig. 2

| Figure 15. Frederic Church, Storm in the Mountains, 1847. Public Domain. |

Aftermath and Conclusion

As Albert Pinkham Ryder aged, he seemed to dwell more and more on death and on his own demise. This may help explain why he chose to live modestly and was obsessed with his artistic legacy. Late in life, he told a visitor to his studio, “The artist needs but a roof, a crust of bread and his easel, and all the rest God gives him in abundance” (Ryder 1905, 10-11). However, even though Ryder lived without physical comforts, this was by choice, not by necessity. During his lifetime, many of Ryder’s pictures sold for in excess of a thousand dollars, and he had “ready buyers for his works even before they were far along on the easel, [and] even if he lacked the ability to bring them to completion” (Broun 1989, 138). In fact, his most financially rewarding work turned out to be Death on a Pale Horse. The artist’s friend (and occasional dealer), Charles Fitzpatrick, left this account:

[Around 1910] I had an office on Broadway. [A collector] who was gathering quite a few of [Ryder’s] pictures had one on the next block. We would meet occasionally, and he would ask me how the old man was, if he was working, etc. … [At one of our meetings] I told him a man from Brooklyn called quite a few times lately who was interested in the Race Track picture. He immediately became interested (I noticed this) and asked how much Ryder was asking for it. I told him I thought seven thousand dollars, and the man was coming in a few days to close the deal. The collector was down in a few days and closed with Ryder for seven thousand five hundred dollars. … The collector was a good sport and had plenty of money … [he] was placing his money on the future market” (Fitzpatrick 1984, 11).

Around the same time, the house in which Ryder lived on Fifteenth Street was closed for remodeling, and he moved a block away to a two-room flat on Sixteenth Street. His health quickly declined, and he was taken to Saint Vincent’s Hospital in Greenwich Village for four months. When he was finally released, Ryder was frail and had nowhere to go, so his friends, the Fitzpatrick’s offered to take him in at their new home in Elmhurst, on Long Island (fig. 16). He lived there in seclusion for a little over a year, when he finally passed away March 29, 1917, a week after his seventieth birthday. In the end, Death and his pale horse finally, inevitably, caught up to Albert Pinkham Ryder as well.

Figure 16. The house where Ryder died 9103 50th Avenue, Elmhurst, New York, 2023. |

About the author: James W. Ellis, PhD, JD, is an freelance writer and a former Research Assistant Professor in the Academy of Visual Arts at Hong Kong Baptist University. Before moving to East Asia, he lived, worked, and was educated in the State of New York, which remains his primary research interest and passion.

Adams, Laurie Schneider. Art Across Time. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002.

American Classic Pedigrees. Hanover (USA). (2023). Retrieved from http://www.americanclassicpedigrees.com/hanover.html

Bailey, Martin. “Ten Myths about Vincent van Gogh.” The Art Newspaper (2019). Retrieved from: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2019/12/06/ten-myths-about-vincent-van-gogh

Barnes, Amanda and Juliet Wright. The Butcher Boys: Part One – The Making of the Brooklyn Stable. Lulu, 2018.

Broun, Elizabeth. Albert Pinkham Ryder. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1989.

Burke, Edmund. A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. London: Dodsley, 1757.

Caron, David. “Four Horsemen.” Irish Arts Review 36, No. 2 (2019): 116-121.

Cole, Mark. “Symbolism on the Race Track.” The Race Track (Death on a Pale Horse). Cleveland Museum of Art (2023). Retrieved from: https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1928.8#

Considine, J. S. “The Rider on the White Horse.” The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 6, No. 4 (1944): 406-422.

Dillenberger, Jane and Joshua C. Taylor. The Hand and The Spirit: Religious Art in America 1700-1900. Berkeley: University Art Museum, 1972.

Eisler, Robert. “Danse Macabre.” Traditio 6 (1948): 187-225.

Ellis, James. “Forest Cathedrals: ‘The Hidden Glory’ of Hudson River Landscapes.” Journal of Religion & Society 21 (2019): 1-20.

Evans, Dorinda. “Albert Pinkham Ryder’s Use of Visual Sources.” Winterthur Portfolio 21, No. 1 (1986): 21-40.

Evergood, Philip. “The Master’s Faithful Servant.” Archives of American Art Journal 24. No. 3 (1984): 5-8.

Fitzpatrick, Charles. “Albert Pinkham Ryder.” Essay in the collection of Harold O. Love, Tucson, Arizona. Microfilm in Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Reproduced in Archives of American Art Journal 24. No. 3 (1984): 8-15.

Fitzpatrick, Charles. “Albert Pinkham Ryder.” Archives of American Art Journal 24. No. 3 (1984): 8-16.

Flagg, Jared. The Life and Letters of Washington Allston. New York, 1892.

Goodrich, Lloyd. Albert P. Ryder. New York: Braziller, Inc., 1959.

Goodrich, Lloyd. “Realism and Romanticism in Homer, Eakins and Ryder.” The Art Quarterly 12 (1949).

Hecimovich, Gregg. "The Cup and the Lip and the Riddle of Our Mutual Friend." ELH 62, No. 4 (1995): 955–977.

Holbein, Hans. “The Noblewoman, from The Dance of Death.” (ca. 1526). Retrieved from: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/336311?when=A.D.+1400-1600&ft=dance+of+death&offset=0&rpp=40&pos=5

Homer, William Innes. “Albert Pinkham Ryder.” Art Journal 50, No. 1 (1991): 86-89.

Homer, William Innes. “Ryder in Washington.” The Burlington Magazine 103. No. 699 (June 1961): 280-283.

Homer, William Innes and Lloyd Goodrich. Albert Pinkham Ryder: Painter of Dreams. New York: Abrams, 1989.

“Hotel Albert 1882-1976 Greenwich Village.” TheHotelAlbert.com (2011). Retrieved from: http://thehotelalbert.com/history/albert_pinkham_ryder.html

Hyde, William. “Albert Ryder as I Knew Him,” Arts 16, No. 9 (1930): 597-598.

Kelly, Franklin. Frederick Edwin Church. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1989.

Kuspit, Donald. “Albert Ryder’s Expressiveness.” Jahrbuch für Amerikastudien 8 (1963): 219-225.

Milliken, William. “’The Race Track,’ or ‘Death on a Pale Horse’ by Albert Pinkham Ryder.” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 15, No. 3 (1928): 65-71.

Muybridge, Eadweard. Muybridge's Complete Human and Animal Locomotion. New York: Dover, 1979.

National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame. Hanover (KY). (2023). Retrieved from: https://www.racingmuseum.org/hall-of-fame/horse/hanover-ky

Novak, Barbara. American Painting of the Nineteenth Century. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1969.

Polistena, Joyce. “The Unknown Delacroix: The religious imagination of a Romantic painter.” America Magazine (2009). Retrieved from: https://www.americamagazine.org/issue/700/art/unknown-delacroix

Ross, Zachary. “Linked by Nervousness: Albert Pinkham Ryder and Dr. Albert T. Sanden.” American Art 17. No. 2 (2003): 86-96.

Ryder, Albert Pinkham. “Joan of Arc.” Microfilm. Washington, D.C.: Archives of American Art, D181, frame 608.

Ryder, Albert Pinkham. “Paragraphs from the Studio of a Recluse.” Broadway Magazine 14 (1905): 10-11.

Sherman, Frederic F. Albert Pinkham Ryder. New York, 1920.

Soby, James T. and Dorothy C. Miller. Romantic Painting in America. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1943.

Taylor, Kendall. “Ryder Remembered.” Archives of American Art Journal 24. No. 3 (1984): 2-4.

Ziff, Norman. “Mortimer’s ‘Death on a Pale Horse,’” The Burlington Magazine 112. No. 809 (1970): 529-535.

No comments:

Post a Comment