Copyright ©2021 All rights reserved by the author.

|

Walter B. Gibson, circa 1965. Photo courtesy of William V. Rauscher |

Walter Brown Gibson was an American literary dynamo, and he was a man of unquestionable artistic creativity, vision, and immense versatility. And so it was Gibson who forged the modern world's first great superhero, called The Shadow.

Master stage magician, top-notch true crime reporter, and word-puzzle expert and mystery writer, par excellence, only give a vague description of who the perennially brilliant Gibson was. Gibson's origins, achievements, and life deserve special attention to properly note his incredibly complex story. Gibson was, after all, a very cagy and competent illusionist. And so we must be careful, as students of history, to sharply look with eagle eyes beneath the veneer of a man (whose persistent modesty) always obscured the giant of who he actually was. Let us remove for your eyes the crafty clouds shielding the genius of Walter Brown Gibson. Let all who inhabit our twenty-first century know Gibson, as man and artist…let our show begin!

The curtains first opened for Walter Brown Gibson on the stage of life on September 12, 1897, at 2 PM (Shimeld, 11). Gibson's mother, May Whidden Gibson, gave birth to her son Walter at the family's somewhat lavish two-story Tudor style house, located at 707 West Philellena Street, in Germantown, Pennsylvania (Shimeld, 11-12). May Whidden Gibson's paternal family lineage and history could "…be traced as far back as the flight of the Pilgrims to America on the Mayflower…" (Shimeld, 8). Gibson's father, Alfred C. Gibson, had served as a young soldier and clerk in the Union Army during the American Civil War (Shimeld, 9-10). Walter Brown Gibson's grandfather, Joseph Gibson, also served honorably in the Union Army's 71st Pennsylvania Infantry Division during The War Between the States (Shimeld, 10). It is a point of the ongoing historical debate about Walter B. Gibson's father's genealogical origins. They (the Gibsons) appear to have been migrants from Great Britain to North America, sometime before the Nineteenth Century, and they were ardent followers of the Episcopal Christian Church. When Gibson's ancestors exactly left the British Isles for America is still unknown, but it is presently a matter of much historical probing, as mentioned earlier in this paragraph.

Alfred Cornelius Gibson (1849-1931) "…was noted as the last surviving person who was present during…[President Abraham Lincoln's accused murderers'] conspiracy trials" (Shimeld, 9-10). "Before his sixteenth birthday, Alfred enlisted in the 215th [Pennsylvanian] Regiment Volunteers as a fifer" (Shimeld, 10) before moving on to an orderly's position for Colonel Francis P. Jones and then later becoming a clerk for Major General John F. Hartranft (Shimeld, 10). During the trials, which began in mid-May 1865 and concluded in mid-June of 1865 (Shimeld, 10), the young Gibson reported to Hartranft on the prisoners, conversed with witnesses, listened to the trials' legal proceedings, and he played his musical instrument (Shimeld, 10). The elder Gibson patriarch would never let his magician son forget about Lincoln's tragic assassination. Nor would Alfred C. Gibson let Walter Brown Gibson lose historical perspective on the Lincoln assassination's turbulent and notorious aftermath, its hugely enduring effect on Alfred, personally, and on the American nation as a whole (Shimeld, 9-10). A. Cornelius Gibson painstakingly recorded the minutia of the history-making trial several times for both his son and others throughout his long life (Shimeld, 9-10).

Following his honorable discharge from the Union Army in 1865, Alfred C. Gibson resumed his academic studies, graduating from Central High School in 1867 (Shimeld, 11). Using an esteemed letter of introduction from his former mentor and Army superior General Hartranft, young Gibson Sr. could secure a decent job with a Pennsylvania gas fixture firm (Shimeld, 10-11). Alfred Gibson was to professionally and financially profit in the gas fixture industry, eventually opening his own private gas fixture company and factory in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania called Gibson's Gas Fixture Works (Shimeld, 13), which was a dynamic, lucrative business operation. Gibson's company quickly transitioned from the manufacture of gas fixtures to electrical ones at the turn of the Twentieth Century (Shimeld, 13). Walter Brown Gibson’s father, Alfred, was one of the most successful, competent and forward-thinking businessmen in the city of Philadelphia (Shimeld, 13-14).

Alfred Gibson's professional and financial success in the gas and electrical businesses led him to build and to buy a larger and more ornate mansion (at 707 Westview Avenue) for him and his family to inhabit (Shimeld, 14). Their new home was close to their first (Shimeld, 14). The twelve-year-old Walter Brown Gibson enjoyed a happy and prosperous childhood at both residences. Walter B. Gibson would recall this fact recurrently throughout his long life (Shimeld, 15). It seems Walter Gibson was a hungry and ambitious reader from early childhood. Gibson "…often referred to himself as a teenage bookworm" (Rauscher, 1). The young Walter Gibson "…also developed a very early interest in the art of magic" (Rauscher, 1). In 1905, while visiting at a celebration in Manchester, Vermont, the eight year-old Walter had his first exposure to stage magic (Rauscher, 1).

"During the party games that followed, he [Walter] was given a string to follow and [was] told there would be a surprise for him at the end of it" (Knowles, 1). There was a trick box at the end of the string for Walter to find (Knowles, 1) and "…, and so started his life-long interest in magic and mysteries, (Knowles, 1). Walter exhibited tremendous writing talent early, getting his first literary piece published in 1905, while eight years old, in Saint Nicholas Magazine (Rauscher, 1). It was a very clever riddle that Walter's rich and cryptic imagination created all by itself. It read as follows: Change this figure (4) to another system of notation, and it will give you the name of a very old plant" (Rauscher, 1). The answer to young Walter's word query was "ivy," written in Roman numerical form as "IV." Walter had made a very small but meaningful artistic splash in the prestigious publication and (he) had officially joined the childhood ranks of William Faulkner, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Edna Saint Vincent Millay. They all were also published as kids in Saint Nicholas Magazine (Rauscher, 1). The eight year-old literary phenomenon, who hailed from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, had called his novel verbal puzzle appropriately “Enigma” (Tollin, 127).

Thus, from Walter Gibson's very fortuitous year of 1905 and forward, he had (knowingly or not) carefully mapped out his career path from an early age. His drive and success came about from his persistently insatiable and eclectic appetite for book learning. It also began from an individual work ethic that was literally second to none. These two vital and primal aspects of Walter Brown Gibson's protean personality would be fearlessly combined (almost alchemically) with Walter's incredibly fertile imagination. From Walter's eighth year of age and to his very end, he would become a man of big ideas, and he would rapidly and permanently transform himself into a bold literary visionary. For endless critics and naysayers of artists, Walter would prove them all wrong. In fact, Mr. Gibson did so regularly, and Walter would dramatically alter the world's literary landscape forever.

Young Walter (unusually curious for a child) became obsessed with magicians and magic tricks…" Throughout his early teens, Gibson devoured all he could find out about magic, and [he] spent hours entertaining his family with tricks" (Knowles, 1). In 1912 the fifteen-year-old Gibson "…was seeking out magic shops and he had also developed a passion for mystery books" (Knowles, 1). The youthful Gibson proved to be a literary dynamo. He published his first mystery tale, "The Hidden Will," in the Wissahickon School Magazine of Chestnut Hill Academy in Philadelphia. Subsequently, Walter published his second mystery tale in 1916, as a student at the Peddie School, in Hightstown, New Jersey (Knowles, 1). Walter's story was called "The Romuda," It won him a prestigious writing award, earning the personal praise of former U. S. President William H. Taft (Knowles, 1). In a face-to-face acknowledgment to high school student Gibson, Taft remarked to Walter, "I hope your story will be the beginning of a long literary career" (Knowles, 1). These experiences bolstered tremendously Walter’s self-confidence as a short story writer when he entered into undergraduate study as a freshman at Colgate University, after Gibson earned his diploma from the Peddie School in 1916 (Knowles, 1 and Shimeld, 23).

Walter Gibson grew to be of medium height, with a build both lean and strong. His large, bright blue eyes resembled two sapphire lanterns, which generated both immense cleverness and mischief for all who looked in them. Walter's very animated and benevolent demeanor was the one that people remembered about him. Gibson used his magic shows to electrify friends and fans alike with his innate positivity and style. Walter's amiable personality was further intensified by his erudite and glowing charisma. Gibson had thick, wavy, light brown hair, perennially and neatly combed back over his crown.

Between his senior year at the Peddie School and his entry into Colgate University, Walter wrote and published several professional-grade instructional articles for The Sphinx magic magazine (Mayne, 1). Moving on to college, Walter eagerly filled his insatiable intellect by thoroughly studying "…Greek, Latin, rhetoric, French, public speaking and biology" (Shimeld, 25) while he was a student at Colgate University, in Hamilton, Madison County, New York (Knowles, 1). Walter even spent his summer preparing for war at the Plattsburg Military Training in Plattsburg, New York (Shimeld, 24). World War I was on and the very bloody conflict involved tens of thousands of American doughboys fighting in the European Theatre.

His ROTC-like soldering drills in upstate New York Gibson took seriously, and he was very attentive in performing his assigned tasks (Shimeld, 24-25). Very luckily for Walter B. Gibson, "The War to End All Wars" terminated in late 1918, allowing the young man to focus on his college studies and magic tricks in peace. It is noted here that from September 12, 1918-December 18, 1918, Walter Brown Gibson did enlist and serve in the U. S. Army successfully as a private (Shimeld, 27). Walter was honorably discharged from military service because the First World War had ended (Shimeld, 27), thus preempting any possible deployment the patriotic Gibson may have had to Europe from his American homeland.

Returning eagerly to college in January 1919, Gibson continued to religiously dedicate himself to his academic pursuits and his study of prestidigitation. He participated skillfully and incessantly in Colgate’s Music Club by doing many well-received sleight-of-hand presentations prior to concerts, before then joining the school’s Biological Society, to satisfy his scientific curiosities (Shimeld, 26).

Upon his successful completion of the spring 1919 semester at Colgate University, the intrepid Gibson did the unthinkable, withdrawing from college before the commencement of his senior year (Knowles, 1 and Shimeld, 28). Whether or not it was Walter's artistic leanings or very independent spirit that caused his premature departure from Colgate, he did leave there on his own accord, without any outside influence from anyone. Walter was a very popular student at Colgate University…but the change was in the air for Mister Gibson. With the Great War behind him and stellar grades under his belt, Walter Gibson seemed to have emotionally outgrown the many quotidian drudgeries of academic life, “Gibson felt that he had gained all the knowledge he could and [he] decided to leave college to reconstruct his life into, what he felt to be, something more beneficial,” (Shimeld, 28).

Gibson followed his sudden scholastic exodus by swiftly deciding, "…to join a carnival and perform magic" (Knowles, 1). Walter Brown Gibson was now on the move, and the terrific and steady momentum he had carefully and fearlessly gathered in his youth and as a teenager was firing away in truly volcanic fashion. Yet the young man Gibson was had only begun to work his miraculous sorcery. America and the world beckoned to Walter, and Walter would not scoff at or deflect the truly great opportunities that were laid before him.

While performing as a seasonal illusionist at the carnival, Gibson met and befriended many professional magicians (Mayne, 2). Gibson's first real job was selling insurance, while he applied for writing work with various Philadelphia newspapers (Mayne, 2). Walter continued to write behind-the-scenes and how-to articles about legerdemain and parlor games for both The Sphinx and Magic World magazines (Mayne, 2). All Gibson's writing was much respected. In the summer of 1919, Walter received a letter of high praise from Sphinx editor Dr. A. M. Wilson, who was very enthusiastic about Gibson's excellence in scripting contributions to his periodical (Shimeld, 28).

Gibson's terrifically steadfast work ethic (clearly instilled in him by his father Alfred) and his constant devotion to achieving superb literary craftsmanship were paying off because, in 1920, The Philadelphia North American hired Gibson as its newest cub reporter (Mayne, 2). During a local bridge collapse shortly afterward, destiny came knocking for Walter Brown Gibson (Mayne, 2). Veteran journalists were called away from the office to cover the story (Mayne, 2), and Walter, the novice reporter, was left behind to "…man the office" (Mayne, 2). At this precise moment, President Warren Harding had arrived in Philadelphia (Mayne, 2), and his staff contacted the North American to be interviewed (Mayne, 2). Walter serendipitously got his first big career break, and he questioned the sitting American President (Mayne, 2 and Shimeld, 35). "The interview went very well" (Shimeld, 35), and Walter Gibson garnered another huge feather in his professional cap. A year later, in 1921, The Philadelphia Evening Ledger hired Gibson as a full-time journalist (Mayne, 2).

At the Evening Ledger, the twenty-four-year-old Walter Brown Gibson was given a greater chance to blossom than his former writing position with the North American (Mayne, 2). "The new job provided him [Gibson] an opportunity to be more creative, and he even began making crossword puzzles, which were a novelty back then" (Mayne, 2). Walter's popular daily column with the North American was called "After Dinner Tricks," wherein each column focused upon describing fully a single magic trick and its procedure, to be performed by readers in their homes (Mayne, 2). After Dinner Tricks had a very successful five-year run (Mayne, 2), and selections from it were compiled into a book by Walter, along with Practical Card Tricks, with both publications being printed and sold together, lucratively in 1921, with much fanfare (Shimeld, 35).

At this time, Walter was again at it, writing his mystery stories for magazines such as True Strange Stories (Knowles, 1) and successfully selling them. Gibson in the very early 1920s (called The Jazz Age) hustled ferociously like the busy, busy bee he was, attending major magic conventions in Philadelphia (Knowles, 2) and hobnobbing with and writing about the world's biggest names in the sleight-of-hand business, including the immortal Harry Houdini, Howard Thurston, Harry Blackstone and the very much-esteemed Joseph Dunninger (Knowles, 2). Gibson was selected by Houdini and others to ghostwrite articles and books on magic (Knowles, 2). These books were published under numerous pennames (Knowles, 2) and they proved Walter Gibson to be a literary hotshot.

From the mid-1920s to 1931, Walter wrote special syndicated features for the Philadelphia Evening Ledger (Knowles, 2). Gibson designed and contributed more than 2,000 crossword puzzles in the daily paper from 1924-1931 (Rauscher, 2). Walter was a brilliant and natural puzzle builder, and his work was very well respected in the United States because Gibson "…helped popularize the crossword puzzle for all time" (Rauscher, 2). Walter Gibson's other esteemed articles and featurettes for these papers included numerous and well-known IQ tests, riddles, brain-teasers, and articles on diverse subjects like human enigmas, miracles, card tricks, and games (Knowles, 2 and Rauscher, 2). Walter was the proverbial "man on fire," and his reputation as a versatile and highly skilled American writer was swiftly growing. Walter clearly was (at this point) on the rise, and his study of Greek and Latin at Colgate University had certainly not gone to waste…nor was his craft and deep insight of stage magic and illusion.

During his early days as both magician and newspaperman, Gibson met mystery fiction's greatest ever writer, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, in June 1922 (Shimeld, 88). The encounter occurred "…at an annual S. A. M. dinner in the New York City McAlpin Hotel" (Shimeld, 88). It was Harry Houdini (a close mutual friend of both) who "…had introduced the two authors" (Shimeld, 88). Houdini, as a liaison, was thus responsible for one of the most historic and significant encounters in literary history. This was so because A. Conan Doyle was the world's leading and most revered writer of detective fiction during the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries (the sole and brilliant originator of Sherlock Holmes) and Gibson. They, a decade later, would single-handedly create The Shadow and would go on to become (in the eyes of many literary critics) Doyle's undisputed artistic successor. Did Walter Brown Gibson and Arthur Conan Doyle swap artistic ideas concerning the composition of detective fiction as they conversed in 1922? Though scarce on this exact meeting, documentary evidence does actually exist, and I plan to probe it further in future writings. Gibson’s personal and one and only interaction with Doyle was apparently a pleasant one, for no biographical information available counters this assumption, especially information written down by Gibson’s historically accurate scholar and scribe Thomas J. Shimeld.

Gibson's thoughts on Houdini (however) are well noted concerning Walter's conference with A. C.

|

| The Shadow. 1994 film. Universal Pictures Co. |

Doyle. Gibson said in retrospection that Houdini presented him (to Doyle) as "an up and coming magical writer" (Shimeld, 88). "That was Houdini's way to flatter people when they deserved it. In return, he [Houdini] expected people to flatter him when he deserved it. Houdini was truly reciprocal…" (Shimeld, 88). It seems certain that Walter Gibson saw a somewhat opportunistic side of Houdini's personality, which Houdini, always the standout but careful salesman, shrewdly hid from his public. Gibson obviously did not let the petty side of Houdini's persona ever get the better of him, for they would both frequently collaborate on many stage magic and illusion projects together until Houdini, the world's best and most daring escape artist, died abruptly and unexpectedly on October 31, 1926 (Shimeld, 57).

By 1931, America's Great Depression was in full swing, almost two years after its initial economic blight and catastrophe had swept the country. Every American citizen was in dire need of an escape from the exacerbating and painful misery of those troubled days. The country responded in three major ways. The first task would be for the country to ratify President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's dynamic New Deal programs, which would dramatically revitalize and modernize America's greatly diminished and obsolete socio-economic infrastructure. The second measure would be a drastic promotion of America's national sports, namely baseball, football, boxing, etc. It was safer and more productive for America to keep its population mentally preoccupied with the innocuous but meaningful national pastimes, rather than having its citizenry overwhelmed about widespread food shortages and unemployment.

The third task to accomplish would be handled by America's pulp magazines. These were direct Twentieth Century descendants of the American dime magazines of the Nineteenth Century. This was blatantly reflected in the pulp magazines' prices, which almost always charged only 10 cents for each issue. "The very first [American] pulp magazine was made in 1882, and many different pulps ran till the 1950s" (Degnan, 1). The pulp magazines published many different genres of printed material, including true crime narratives, science fiction, tawdry and salacious sex stories, westerns, detective fiction, and sports stories (Degnan, 1). The publishers of these magazines would also do their part to keep the American mindset off of the doom and gloom of the 1930s and 1940s. Walter Brown Gibson would emerge from the proverbial shadows of obscurity and he would disappoint no one.

Thus, for only a dime, any American could set themselves temporarily free of the terrific burdens of The Great Depression (and World War II) via purchasing a mystery or sports "pulp" by getting lost in an article or a fiction story. "Because pulps were so cheap and affordable, they were one of the main forms of escapist entertainment for the working class, especially since comic [books] and television did not yet exist" (Degnan, 1). Called pulps for the cheap sort of paper they were written on, they slowly changed the style and essence of American popular culture from the late 1800s to the mid-1900s. Gibson's The Shadow and Lester Dent's Doc Savage quickly and permanently became "pop" culture icons of superhero and mystery fiction, and American, and world audiences would become enthralled.

So, in 1931, pulp publisher Street and Smith asked to meet Gibson at their New York City offices to give form and substance to The Shadow (Knowles, 3) who was, at that point, only a grim, ghastly and disembodied voice, who had served to narrate the numerous mystery tales of its well-known Detective Radio Drama series (Knowles, 3). The radio show's narrator was The Shadow. But since the phantasmal voice of the radio show's narrator proved more popular than the actual show with listeners, Street and Smith decided it would be more lucrative to create a detective magazine using the narrator's name, The Shadow (Knowles, 3).

"Gibson happened to be at the right place at the right time…" (Mayne, 1). "The plucky young writer [Gibson] was in New York pitching one of his true-crime stories to the editors, and they wondered if he had the potential to give life to their new idea" (Mayne, 1). As the interview progressed, "…Gibson told them [the editors] about a character he'd been imagining, who had 'Houdini's penchant for escapes, with the hypnotic power of Tibetan mystics, plus the knowledge shared by Thurston and Blackstone in the creation of illusions,'" (Mayne, 1). Smith and Street's editors responded to Gibson's proposal with genuine curiosity (Mayne, 1), and they chose to "…gave him [Gibson] a shot" (Mayne, 1).

With Walter Brown Gibson's first composed pulp novel The Living Shadow finished, his answer to Smith and Street's demands would be total and uncontroversial. The Living Shadow was 75,000 words long, and it sold out immediately (Mayne, 1). In April of 1931, with one fell swoop, Gibson had done what no other writer before him ever did, and perhaps, even dared to imagine (Shimeld, 63). Gibson had single-handedly launched the Superhero Age with the publication of the first Shadow Magazine.

Gibson had entirely surpassed Smith and Street's expectations because, after Gibson's second Shadow novel also rapidly emptied off bookshelves, his editors decided at Smith and Street to revamp Walter Gibson's contract (Mayne, 1) and step up production on The Shadow Magazine, by changing it from a quarterly publication to a monthly one (Mayne, 1). Gibson had no trouble keeping up with the amped-up writing schedule, and he even exceeded expectations again when The Shadow Magazine went from being a monthly magazine in 1931 to a bi-monthly one in 1932 (Mayne, 1). Walter Gibson's intensive creativity was perpetually on fire. And his superbly diligent work discipline, instilled in him by his aged father, Alfred, also had a great deal to do with Walter B. Gibson's success.

The Shadow as a fictional character was promptly and effectively given a colorful origin story and mythology by Gibson (please see the novel The Shadow Unmasks for more information on this topic), who penned all of his Shadow novels under the nom de plume of "Maxwell Grant." The Shadow was, in fact, a WWI superspy and fighter ace named Kent Allard, who, after The Great War, left Europe for Asia. Allard studied there with numerous Hindu and Tibetan gurus and holy men, learning various arcane martial and mystic arts, including yoga, karate, meditation, hypnotism, etc. Allard was also a brilliant college student who deeply studied history, psychology, mathematics, and linguistics. In fact, Gibson's Shadow was the superhero world's foremost authority (perhaps inspired by A. C. Doyle's Sherlock Holmes) on ciphers, codes, and secret writing (please see The Shadow novel The Chain of Death and others).

Meanwhile, Gibson had Allard fake his death in South America and return (incognito) to the United States. Kent Allard (being primarily based on legendary British explorer, surveyor, and cartographer Percy H. Fawcett and famed American escape artist, daredevil, and stage magician Harry Houdini) donned a black slouch fedora hat, black and red cape, and a sinister red scarf (to shield his face from the public) to begin his vigilante war against crime. New York City was the helm of The Shadow's operations (please see The Living Shadow and other novels for more information about this topic), and The Shadow would use his amazing arsenal of eclectic skills to taunt and subvert the criminal underworld, especially when using his phantasmal, haunting laugh in the presence of crooks and lethal, cutthroat masterminds.

The Shadow was a master of stealth, spymastering, and certainly gunslinging. In the hit radio show, sponsored mainly by Blue Coal, he was also a psychic warrior who could "cloud men's minds" (see also the intro to The Shadow Radio Show, starring Orson Welles, Agnes Moorehead, and others). Allard assembled a covert and valued international spy network and took on the very vaunted moniker of The Shadow. He also brilliantly (under Gibson's direction, of course) engineered various aliases that The Batman (his most direct historical and literary descendant) could never keep track of. The Shadow was called Ying Ko by the Chinese, The Dark Eagle (because of his very noticeable aquiline profile and jet-black hair), The Knight of Darkness, The Dark Avenger, The Master of Darkness, and Lamont Cranston (a wealthy New York City playboy who bore a striking, but coincidental resemblance to Allard himself), just to name a few. The Shadow used his keenly developed spy abilities and uncanny occult powers to battle evildoers and criminals of all sorts, from nefarious mad scientists and deadly mob bosses to lethal, cunning, and fanatical spies and others. All tales and foes Gibson created for The Shadow ubiquitously fell into the category of what literary scholars now call "supercrime," something wondrously forged by Arthur Conan Doyle in his Sherlock Holmes tales, specifically where Holmes dangerously squares off against Professor Moriarty in The Final Solution and The Valley of Fear. No matter how difficult or bleak circumstances ever became for The Shadow while in the midst of combating evil, he always used his mind and grit to defeat his many, many enemies. Arthur Conan Doyle invented supercrime in his Sherlock Holmes novels, and stories and Walter Brown Gibson perfected supercrime in his Shadow ones.

The Shadow skulked silently and secretly about the hidden corners of human vision, only to deftly and mercilessly pounce on and eliminate his venomous adversaries. He did shoot his .45 caliber pistols only when being fired upon. Remember, the 1930s and 1940s America was the brutal era of vicious and homicidal gangsters like Al Capone, John Dillinger, Baby Face Nelson, Bonnie and Clyde, and Mickey Cohen. The common folk of America, stung badly by the economic hardships of The Great Depression, yearned for a crime-fighter whose sense of justice was certain and whose ability to dispense some was unobstructed by political and social grandstanding.

Walter Gibson's Shadow fit the role perfectly, and The Shadow took his crusade around the world to end evil wherever he and his agents had found it. Lester Dent's starkly intrepid and super-intelligent Doc Savage, called The Man of Bronze, was also a Smith and Street superhero character, who used his super-strength and outstanding intellect to battle "super-criminals" on a global level, in a manner very similar to that of The Shadow, written by Walter B. Gibson. The Shadow was a crime-fighter who pushed his mind and body to their limits to adequately confront crooks and to turn them on their heads. The Shadow stories of Gibson had compelling, well-written plots and characterizations, great descriptive scenes and language, and terse and snappy dialogue. In the pages of The Shadow Magazine, Gibson was on a literary roll, and his fans were routinely left with their mouths agape. Gibson's high quality of writing spoke for itself.

|

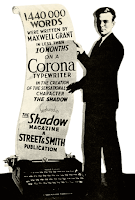

| Walter B. Gibson, 1933. Photo courtesy of Smith-Corona, Inc., all rights reserved, 2021 |

The Shadow was (from a literary perspective) the most entirely nuanced and original superhero in pulp and comic book fiction. Perhaps, after ninety incredible years, The Shadow still is. Historical archivist and investigator Aleta Mayne notes that "Other crime-fighting vigilantes---particularly Batman---cut their capes from the same cloth as him" (Mayne, 1). Gibson's stellar run on The Shadow lasted fifteen brilliantly dynamic and prodigious years (Mayne, 1). He authored 283 Shadow pulp novels out of the current 326 Shadow novels (Knowles, 1 and Mayne, 1). This figure amounts to a total of almost 87% of all Shadow novels (including novellas and short stories, also). Gibson's internationally renowned prolificacy garnered him the personal paid endorsement of American typewriter manufacturer Corona in 1933 (Knowles, 3). Why should anyone be surprised? During Walter Brown Gibson's superbly productive lifetime, he wrote: 187 books (primarily mystery fiction and instructional books for stage magic, but also various books on history and the occult), 668 newspaper and encyclopedia articles, 48 separate and syndicated feature newspaper columns, 394 comic books and strips and 147 collaborative radio scripts (Mayne, 2-3). The Washington Post approximated in 1978 that Walter Brown Gibson had written a total of 29 million words during his lengthy writing career (Mayne, 3). Walter B. Gibson was (as a master scribe specifically) no slouch at all.

Years after Walter's death in December of 1985, his son Robert (a very-esteemed medical doctor and psychiatrist from Maryland) would comment, "My father first wrote of The Shadow in 1931, when I was just six years old. His workroom was next to my bedroom. The writing schedule demanded almost round-the-clock typing as I went to sleep. It was pleasant to know he was nearby" (Gibson, ix). Robert Gibson continued, "My bedtime stories were the plots of Shadow novels in their embryonic stage. Of course, other stories poured from my father's fertile, creative mind. Among them were the adventures of a remarkable family of fish, which should have been published" (Gibson, ix). Even during a hectic workday, Walter's very kind heart and quite a mischievous mind never divided themselves. Walter had shrewdly made use of his family time by spending his evening hours eagerly relating his Shadow story ideas and characters to young Robert while simultaneously expanding on them. Walter was a father firstly and a writer secondly. Work would not interfere with Walter's family life. This is because Walter had skillfully managed to marry the two into a benevolently cohesive and well-organized whole. Could Shakespeare himself have achieved such a feat in his own lifetime? One can only hypothesize about that possibility…

Writing full-length novels at breakneck speed certainly was not easy, even for a thoroughbred wordsmith like Walter B. Gibson. But Walter always managed to stay well ahead of his deadlines (Shimeld, 70). Walter did not use a specific literary formula for composing his Shadow stories. Instead, Walter would develop story concepts organically. These made The Shadow novels generally unpredictable with their plotlines, producing narratives much more suspenseful and exciting for readers. Walter was a master technician of science fiction and mystery literature, and he was not a commonplace assembly-line writer. "Plots would come to Gibson from any number of places: newspaper articles, a paragraph in the encyclopedia, anywhere" (Shimeld, 71). Walter was a painstaking literary researcher who premeditated storylines way before their due dates (Shimeld, 71). This very often entailed Gibson personally visiting different American cities and carefully recording their place names and geographical landscapes (Shimeld, 71) so that Shadow books were very realistic in as many details as possible for readers. Walter's approach to composing made The Shadow a much more national literary and popular culture icon. The Shadow appeared in all major American cities from coast to coast, cities that Walter Gibson intentionally and physically traversed. Shadow fans in Chicago, New York City, and Phoenix, Arizona, would be more motivated to read Shadow pulps because The Shadow's stories were taking place right in their own hometowns. "The Shadow…traveled to Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago, Miami, and New Orleans" (Shimeld, 71). Smith and Street Publishing commercially motivated this "…so that the company might publicize the magazine in those areas" (Shimeld, 71). Money in the world of print media decides which way that particular planet always spins. Smith and Street was very effective in using Walter Gibson's The Shadow to efficiently fill its own publishing house's coffers at every twist and turn.

Despite all the toil that Walter was experiencing as a writer of fiction prose, Gibson was doing what he loved most, writing yarns as original and unique as are the ripples in the sea. Walter Brown Gibson also enjoyed getting paid for his services, saying, "Output means money. If you don't write stories, you can't sell them" (Shimeld, 70). But it was Gibson's salary from Smith and Street that was perennial of secondary importance to him. Walter positively lived and loved to write, whether the material was fiction or not.

The art of writing seemed to elevate Gibson's soul and mind to intellectually and emotionally more lofty and deeper places and conditions. Gibson found that the aesthetic aspects of writing mentally made time come to a sort of stop (Shimeld, 117), and these aspects of writing enabled him to think in much more visionary and richer ways (Shimeld, 117). For Walter B. Gibson, composing words for his novels transported his spirit and memory to an unearthly, inspired place. This was a realm where his ideas for language and storytelling relieved his psyche and his body of any emotional and physical weaknesses or hindrances they both may have had (Shimeld, 117). Writing for Gibson was both an act of love and an act of catharsis (Shimeld, 117). Writing a story of fiction was also something that suggested supernatural causation (Shimeld, 117). Walter took the craft of writing seriously, and he was consciously and creatively positing that writing was quite likely a divine act, one in which it connected him to his Christian God.

"Memory does not only contain things we remember from the past. It contains events of the future as well…Often, when writing mysteries, I picked up ideas psychically of things that really did happen in the future,"' Gibson related to journalist Claire Huff in a 1976 interview (Shimeld, 117). For example, in the 1942 comic strip Bill Barnes America's Air Ace, Walter Gibson (who was guest scripting for Bill Barnes at the time) has one of his characters, Doctor Blannard, reveals to Bill Barnes that he has just invented an explosive device that harnesses U-235 to be used against one of Bill Barnes' enemies (Shimeld, 117). Walter was contacted by Federal officials immediately after that, and he was informed to refrain from mentioning U-235 in any of his future works (Shimeld, 117). Walter B. Gibson fully cooperated with the agents "'in the interests of war security'" (Shimeld, 117). Thus, at the height of America's involvement in WWII, Gibson had accurately predicted the atomic bomb's creation three years before anyone else had (Shimeld, 117). Other such psychic incidents concerning W. B. Gibson were not isolated ones at all (Shimeld, 117-118) and are fully and factually recorded. Ironically, though, Gibson (the very cynical and perceptive stage magician) did not identify himself as a mystic. He identified himself as a creative artist who personally believed in God and the supernatural; however abstract and sublime these notions are for the human mind to grasp.

During turbulent years of World War II (1941-1945), Gibson kept the sci-fi-adventure story genre thriving for Americans by scripting one excellent Shadow novel after the other. "Up until March of 1943 he [Gibson] pumped out 24 pulps per year…" (Mayne, 3) "…but he did eventually slow back down to one per month" (Mayne, 3). By 1947, Walter B. Gibson was writing only one Shadow novel every other month (Mayne, 3). Then, by the autumn of 1948, Gibson was writing The Shadow Magazine was a quarterly until the summer of 1949, when Street and Smith Publishing finally terminated publication of The Shadow. Increasing competition from comic books and a concerted effort by right-wing extremists in the American government such as Senator Joseph McCarthy made selling pulp magazines in the United States very difficult. As the year 1950 approached, The Shadow's days seemed to evaporate. After, Gibson sued Street and Smith for his royalties on The Shadow amounting to $40,000.00 (Knowles, 5). Walter Gibson's creation The Shadow ceased to be…or so everyone thought. Gibson (by the late 1940s) had already moved on to other writing projects…but The Shadow was not dead…, and neither was his creator, "Walt" Gibson.

This temporary lapse in American pulp superheroes caused a gaping hole in the genre's writers' market. It is no historical coincidence that English writer and former officer for British Naval Intelligence Ian Fleming (Britannica, 1) emerged on the global literary scene by debuting his famous Agent 007 James Bond in 1953 (Britannica, 1). James Bond was the chronological successor pulp hero to American ones The Shadow and Doc Savage, repeating Walter Brown Gibson's pattern with Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes in 1931. In April of that year, The Shadow had made his grand premiere on the world's stage. His entrance was bolstered by the fact that Doyle's Sherlock Holmes had stopped being actively written and published by 1927 (Gardiner, 323). Doyle himself died in July of 1930 (Gardiner, 323). The Shadow Magazine's circulation numbers hence benefitted from Sherlock Holmes' absence from the literary world. But this fact (in no way) undermines the quality of The Shadow's literary significance or Walter B. Gibson's standing as a writer of great yarns. The Great Detective's influence on The Master of Darkness will forever be debated in literary circles and comic book conventions. And only a reader can decide for him or herself which character they prefer over the other.

From 1946-1961, Walter Brown Gibson was on the move again. "He [Gibson] was moving more and more into the book field, while at the same time (in the 1950s) creating true crime stories for Fact Detective Magazine" (Rauscher, 4). The Shadow was for fifteen consecutive years Walter's main source of income. Gibson had some severe trouble transitioning from pulp writer to book writer. Unfortunately for Gibson, the reasons for this were clearly not professional ones, and they were familial ones.

As The Shadow and his alter ego Kent Allard temporarily retreated to the popular culture background, Walter Gibson was slowly and silently experiencing the painful throes of his second failing marriage, to one Julia Gibson. Walter did not expect his wife to leave him (Shimeld, 98). The main culprit seems to have been Walter's artistic aloofness, which steadily increased as he grew older (Shimeld, 98). Walter's divorce became inevitable as the emotional disconnection between him and Julia widened over the years of their relationship. "By December of 1948, Julia and [Walter] Gibson were divorced" (Shimeld, 97). Walter fell into a deep melancholy under the hefty strain of his imploded marriage to Julia and his gradually diminishing income (Shimeld, 98). "With no time to prepare mentally for a break-up, Gibson plummeted into a depression" (Shimeld, 98).

Walter did not remain in the doldrums for long. "On August 24, 1949, Gibson married his third wife, Litzka Raymond Gibson" (Knowles, 8-9). Litzka was the widowed wife of the very talented stage magician, The Great Raymond (Knowles, 9). Litzka was an excellent harpist, singer, and magic performer (Knowles, 9 and Shimeld, 120-121). "Litzka was a devoted wife who was constantly attending to Gibson…" (Shimeld, 120). The numerous "…encounters with Litzka's graceful singing, and beautiful presence would always have a positive effect on Gibson's mood…" (Shimeld, 120). Walter Brown Gibson frequently called his third and final wife "Angel" (Shimeld, 120). "The two [Walter and Litzka together] shared a life of magic and a love for the mysterious" (Shimeld, 120). Litzka and Walter Gibson's radiant and enduring love thrived for thirty-six healthy and romantic years until Walter's passing in 1985. Walter knew he had found his true love in Litzka, and the two did not part for as long as their lengthy marriage lasted. Walter doted on Litzka as she would dote on him while they were together.

Once Gibson had snapped loose from his mid-life funk, he resumed his writing career with vigor and skill. Walter's practical attitudes, apart from his exalted ones, were equally important to him. Walter once commented, "…one source of inspiration is a good, swift, self-delivered kick in the pants" (Rauscher, 5-6). Gibson was once accused of not needing the inspiration to fuel his work on fictional and factual prose (Rauscher, 6). The gentleman said to Gibson, "Maybe you don't need much inspiration, writing for your market" (Rauscher, 6). Walter masterfully responded, "I need just as much as if I were writing for another, because I'm not writing for any market. I have always written for readers, and I have found it valuable to continue that policy. It keeps a writer from going stale, enables him to follow any trend, and sometimes to start [a new] one" (Rauscher, 6). Translated critically for literature and history, Walter was saying that (concerning his writing) he wrote for himself firstly, and for others, secondly. Walter was writing his fiction pieces and non-fiction ones for the common man and woman. No one reader for Gibson was better than another to him, with the possible exception of himself. No one reader was less critical for Gibson than any other, again, with the same possible exception. This type of work ethic clearly imitated Walter's egalitarian views of people. His son, Robert, once said, "My father knew every famous magician and had personal contact with many prominent writers, but their prestige or prominence never drew him. He could spend an hour talking with the bellman of a hotel. He simply enjoyed people" (Gibson, x). But Walter Brown Gibson also shrewdly reasoned that if writers cannot please themselves with the individual quality of their work, then they aren't able to please anyone else with their writing, too.

Deadlines from editors never impressed Gibson, simply because his insatiable dedication to writing obliterated deadlines with disturbing regularity. Gibson never missed a single deadline. And yet his writing, whether creative or factual, habitually was thoughtful, intriguing, lucid, and well worded. What more could an editor ask of their writer?

Walter's dear friend, the Episcopal priest and professional magician, William Rauscher, said of Gibson, "Walter was a man who chose interesting side roads instead of a direct route" (Rauscher, 6). When walking (or driving a car), Walter chronically chose the most beautiful or interesting path of travel rather than the most convenient one (Rauscher, 6). Gibson was, after all, an artist at heart and consistently so.

In 1957, Walter Brown Gibson was an editor at Mystery Digest (Shimeld, 127). In post-WWII America, Gibson authored two crime novels, A Blonde for Murder, and Looks That Kill, published between 1946-1948 (Rauscher, 5). These mystery novels sold well, and they are still actively in print today. As the 1960s came into swing, Walter successfully engaged in many profitable writing projects. At the behest of legendary series creator Rod Serling, Gibson scripted (in 1967) original stories for two volumes of the prose-anthologized Twilight Zone (Shimeld, 88), and Gibson repeated a similar feat for The Man from U.N.C.L.E., (Shimeld, 88).

In the early 1960s, Walter composed five novels of the critically acclaimed young adult Biff Brewster books series for the Grosset and Dunlap Publishing Co. (Tollin, 127). He returned to The Shadow with a vengeance in 1963, writing the all-new The Shadow Returns (Tollin, 127). Gibson's comeback Shadow novel was a huge hit, and it unofficially inaugurated the "Silver Age of Superheroes" (1963-1980). A new, vibrant renaissance swept American letters in superhero fiction. Walter B. Gibson and other sci-fi-visionaries such as Marvel Comic's Stan Lee and Jack Kirby were all responsible for it. Walter Gibson was back in the big leagues, but, of course, he had never actually left them. He was simply riding the crest of an incredible literary wave in the 1960s that (genre-wise) had slumped badly to its bottom in the late 1940s. Gibson proved to be an excellent surfer. Walter Brown Gibson would never slide to the literary bottom again. Gibson's unceasing perseverance would keep him afloat for the rest of his life.

Gibson authored a number of popular books on the paranormal and stage magic, including 1966's The Complete Illustrated Book of the Psychic Sciences, co-authored with his wife Litzka, The Complete Illustrated Book of Card Magic, in 1969, Secrets of Magic in 1973, The New Magician's Manual in 1975 and 1980's Big Book of Magic, (Knowles, 7-8). The tremendous esteem of Walter Gibson's writing and sage-deep wisdom of legerdemain and illusion earned him the highest honors by the very respected American Academy of Magical Arts (Knowles, 8), amounting to a Literary Fellowship in 1971 (Knowles, 8) and a Master's Fellowship in 1979 (Knowles, 8).

After 1970, Walter Brown Gibson was not done with his most illustrious literary creation, The Shadow. In 1979 he wrote and published for Conde Nast Publications another adventure featuring The Dark Avenger, entitled The Riddle of the Rangoon Ruby, for The Shadow Scrapbook (Tollin, 127). Gibson also penned the 1980 Shadow tale (also for Conde Nast) Blackmail Bay in The Duende History of The Shadow Magazine (Tollin, 127). Walter Brown Gibson's last published superhero tale came in late December 1980, when he wrote for DC Comics The Batman Encounters---Gray Face (Tollin, 127). The Batman short story Gibson scribed was roughly 6,000 words, and it was printed in DC Comics' exciting Detective Comics Issue Number 500 (Tollin, 127). These excellent prose featurettes firmly demonstrate that Walter Brown Gibson, even in his eighties, had not lost his golden touch for composing highly compelling and riveting works of mystery and adventure fiction.

In 1966, seventeen years after marrying Litzka in 1949, Walter and his beloved bride bought a house in Eddyville, New York (Knowles, 8). The two-story Victorian mansion was initially built in 1757 (Shimeld, 128), but it was later expanded over the years by several different occupants (Shimeld, 128). The Eddyville House rapidly emerged as "…the center for their intellectual and productive life" (Knowles, 8). The Gibsons together meticulously amassed and archived their vast library of over 9,000 books, volumes concerning history, metaphysics, stage magic, language, art, and other assorted subjects (Shimeld, 128). Walter and Litzka would use this library to its fullest potential as writing and reference material to compose their many assorted literary efforts (Knowles, 8). New York State was the focal point of Walter Gibson's life for many decades, so it would remain until his very end.

Walter (as a historian of magic) in the late 1960s came to be interested in Eddyville's rich maritime and shipbuilding past (Shimeld, 141-142). Gibson was inspired by the picturesque Rondout Creek, which his Eddyville home directly overlooked (Shimeld, 141). Walter Brown Gibson joined the local Delaware and Hudson Canal Historical Society (Shimeld, 141). In December of 1970, Walter was designated assistant editor of Then & Now, the historical journal of "D and H," (Shimeld, 142). In the early 1970s, Gibson was elected and served as the Delaware and Hudson Canal Historical Society's president (Shimeld, 142). Under Walter Gibson's tenure, D & H's Museum was created in April of 1971 (Shimeld, 143). "Gibson was well known and well respected within the society" (Shimeld, 142). "He [Gibson] would often perform magic shows at various functions" (Shimeld, 142). Gibson was partaking in a richly fulfilling life that was at once positive and spiritually beneficial for him and others. In all that Walter Gibson did, the creation of artistic and cultural achievements haunted and motivated his soul to move, act, and fashion. Neil Armstrong left his footprints on the Moon. Walter left his footprints in the countless imaginations of writers and artists who were all inspired by him, stage magicians or comic book artists and storytellers. In this capacity, Walter Brown Gibson would even outfox Time itself, and in the process, Gibson would become immortal. Walter's contemporary artists such as the magnificent Dick Tracy creator Chester Gould and later comics and graphics art genius Matt Wagner would all owe something to Walter, whether it was artistic radiance or intellectual variety. Gibson’s stamp of superhero novelty is impressed all over the world and especially in the United States.

Readers should keep in mind Walter is an utterly hard fellow to historically classify, mainly due to the immutable fact that he was an American original. Walter Gibson's titanic reverence for history, art, and language always lies at each of the centers of his Shadow stories, even if all of these elements are not easily apparent in The Shadow. Walter was a consummate literary professional who took great pride in fooling his Shadow fans with literary subtleties and unexpected and brazenly clever story endings. Gibson was a stage magician after all and readers of The Shadow should always be prepared for the unpredictable. Gibson was never static or mundane in his life or in his personality and his Shadow work reflects this truth overwhelmingly.

The historical narrative of Walter Gibson does not end here. I have previously mentioned the very talented and accomplished British pulp writers Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Ian Fleming in this text. They are both listed as topics of interest in the Encyclopedia Americana (alphabetically and accordingly) for their fine literary efforts, namely for their respective creations of Sherlock Holmes and James Bond. Walter Brown Gibson is nowhere to be found in the Encyclopedia Americana for his literary activities as the author and the originator of The Shadow. But, ironically, Walter Brown Gibson is listed in the Encyclopedia America as a historical researcher, as the author of Harry Houdini's biographical entry (Gibson, 455). By hook or by crook, the very, very persistent and habile Gibson would not be overlooked by history. If Walter's superb skills as a composer of fiction were to be overlooked by some, his standout assets for writing non-fiction would not be neglected by others. The short article he writes of Houdini's life is properly detailed and organized. Gibson's writing hits all the high notes, and its subject matter is succinctly communicated and contextualized. Walter Brown Gibson was truly a literary force with which to be reckoned.

Walter Brown Gibson was a man of great personal conviction. He fought and hacked his own swath through the metaphorically bitter weeds, mire, and undergrowth of life. We must remember Walter Brown Gibson's father, Alfred C. Gibson, was a very down-to-earth and pragmatic businessman who was both hardworking and forward-looking. But Alfred was a man who dealt in and thrived from involving himself in facts and non-abstract truths. He was not one to obsess over fanciful matters. Incidentally, Walter Gibson's son, Robert W. Gibson, was a driven, humane, and very competent man of science. Robert Gibson was a man, who like his grandfather Alfred, was not one who dealt in the ethereal realms of fancy and fiction. Perhaps it was his job as a committed and empirically-grounded thinker and psychiatrist that made Robert not indulge in artistic activities, as his father Walter was prone? Historians and others are only left to speculate.

What is clear and self-evident is that Walter was certainly not a man who wasted the rich and inventive imagination God had given to him. Walter Brown Gibson was also a man of action who did not let the grass grow under his feet, especially when earning a living as a writer. He was ambitious enough and clever enough as a man to successfully weave his love of stage magic, history, mystery tales, and wordplay into a mighty and healthy vehicle for making money. His literary legacy as a pulp novelist, true-crime reporter, word puzzle maker, and magic historian unambiguously speaks volumes to Gibson's commitment to himself and others that the human mind was itself a magical instrument, whose limitations are both largely unknown and untested. Walter's feline-like hunger to feed the human mind's curiosity for higher learning, riddles and mysteries was a firm and fixed testament that Walter knew from his earliest age that human beings were beings who had to challenge themselves against riddles and puzzles in order to achieve self-discovery and self-actualization. One's mind could never be idle to gain wisdom for Gibson. A healthy human brain for Gibson was one that questioned the world around it through sound introspection, philosophical debate, and artistic and literary activity, specifically reading and writing. Walter's prolific output as a stage magician, adventure novelist, and word puzzle builder fulfilled much of his quest to awaken the wonder in peoples' souls. For Walter Brown Gibson, a dull mind was one that never forced itself to think. Walter was not boring nor was he unoriginal, be it as a man or as a thinker.

Walter left his family's hallowed ground of Colgate University before he could graduate from there, primarily because of his fierce and feisty self-confidence in himself as a writer and as a magician. We know this because Walter's uncle Frank Gibson was a very respected professor of Greek at Colgate (Mayne, 3). At the same time, Walter's brother Theodore Gibson became a much-lauded instructor there in mathematics (Mayne, 3). Not receiving his college degree from Colgate University did not wound Walter in any way, spiritually or otherwise. Although Walter did not conform to many of his family's norms or expectations, he did inherit from Alfred his tireless work ethic and his penchant for honesty and decency. Walter, in his 88 years of earthly life, never had any conflicts with the law whatsoever. This also speaks favorably for Walter's character.

Walter Gibson was not a spiritually or morally faultless man who inhabited a cosmologically perfect universe. Walter did have some minor personality flaws of his own. Gibson's biographer Thomas J. Shimeld writes of Walter, "He was considered by many magicians to be the '"foremost authority on magic in the world'" (Shimeld, 137). Shimeld continues, "Gibson knew so much about the history of magic, for he lived through the first golden age of the art; no one would argue against his word, even if his word wasn't totally fact" (Shimeld, 137). Walter Brown Gibson, rightly considered the elder scholar-statesman of American stage magic, was, at times, a self-ordained know-it-all. No one can reasonably or factually deny that Walt Gibson was one of the world's most well-read magicians on the history of prestidigitation. But his ego did get the better of him on more than one occasion, precisely when it came to his chosen field of expertise. Walter being his consistently amicable and talkative chatter-box self, always had a yarn to weave. This includes Walter's personal memories of stage magic and stage magicians.

Walter thought any student of stage magic would never argue against his very worthy and capable talent and reputation (Shimeld, 138). But some did (Shimeld, 138). It was Walter's belief that they were not personally there to witness the events as he had been there to see them, so who were they to challenge him? Yet Walter (persistently the cunning master of misdirection) would demonstrate to them his individual recollections of the facts in a historically half-true context and in the form of a biographically half-true but entertaining story (Shimeld, 138). Walter was not above embellishment. And because Walter could and frequently did charm the hearts of many cynical audience members, he was more than often able to prove his point about a particular aspect of stage magic without offending or discouraging the most hardened of critics (Shimeld, 138). If Walter had a point of debate to prove in a discussion of legerdemain, he did so with skill, gusto, and subtlety. Gibson was a magician, once and always.

Gibson was the middle son of his father Alfred's second marriage. Alfred Cornelius Gibson's first marriage yielded three healthy children, two daughters, and a son (Shimeld, 11). Alfred C. Gibson's second wife, May Whidden Gibson, brought forth three healthy sons, Walter Brown Gibson (Shimeld, 11). Although Walter was married numerous times (three to be exact), unlike Alfred, he was the father to just one child, Doctor Robert W. Gibson (Shimeld, 88).

Walter spent the happy, latter years of his life performing magic shows in and around Eddyville, New York, and elsewhere. He was a frequent guest at major comic book conventions in the United States in both the 1970s and until the early 1980s. Walter was also a major participant and lecturer at national stage magic conventions, who often creatively collaborated with his dearly cherished spouse Litzka. Although Walter gave up his habitual and unhealthy cigarette-smoking regimen (at Litzka's prodding) in the 1950s (Shimeld, 127), he did put on much weight from the 1970s forward. By the middle 1980s, Walter, who was often sedentary, was experiencing significant heart difficulties (Shimeld, 151). Walter B. Gibson suffered a horrible stroke on November 7, 1985 (Shimeld, 151). This stroke left him both blind and without the ability to speak (Shimeld, 151). Despite his body and mind being devastated by this vicious stroke, Walter still had his wits about him (Shimeld, 151). But the curtains were drawing to close on Gibson's life. Walter Brown Gibson, the renowned creator of modern superhero fiction and stage magician of the first rank, died on the fateful morning of December 6, 1985, at Benedictine Hospital, in Kingston, New York (Shimeld, 151). Walter was 88 years old.

Though the great man and artist was dead in body, Walter's soul, reputation, and legacy thrive. Litzka and Robert W. Gibson were devastated by Walter's tragic loss. And so was the world. Walter Brown Gibson's family, friends, and fans were legions, and none would ever turn their backs on him or his memory. In the world's two realms of popular literature and stage magic, Gibson firmly remains both an eternal and titanic hurricane of blinding and burning artistic illumination. His light is both far-reaching and unyielding. Writers of superhero fiction, such as myself, personally feel his huge loss and presence, as much in the twenty-first century as fictionalists and stage magicians have felt them in the twentieth. So Walter remains what he always wanted to be: a loving, productive, and innovative writer, performer, and family man…one who loved America and one who loved life.

Walter Brown Gibson was buried in upstate New York at the Montrepose Cemetery of Kingston (Shimeld, 153). He was given an Episcopal Christian funeral and burial service, conducted by his close friend and fellow stage magician, the Reverend Canon William V. Rauscher (Shimeld, 153).

When Walter Brown Gibson died in early December 1985, many historians felt that America's last living link to The Golden Age of Magic was gone (Shimeld, 156). This may well have been true. It could also be very smartly and historically wise to say that when Walter B. Gibson passed from this Earth, one of America's last living links to "The Golden Age of Superheroes" (1931-1950) vanished as well. But what serious and responsible students of history must realize is that though the man is no longer with us, his God-given spirit and mind still are relentlessly pulling us towards him to think, create, and persevere. In doing as much, Walter Brown Gibson not only outlasts Time and Space, but he spectacularly lives on in present-day imaginations, as the vital and almost preternatural artist he was. Walter Brown Gibson is as much a super-heroic inspiration for American artists now as he was nearly forty years ago. Gibson, along with his Shadow, both have finally seen the light of day. History and the world at large have permanently taken note.

Bibliography:

1) Ian Fleming, The Editors, The Encyclopedia Britannica, copyright 2021, Britannica.com.

2) Mai Ly Degnan, Pulp Magazines and Their Influence on Entertainment Today, The Journal of the Norman Rockwell Museum, January 2013, nrm.org.

3) Dorothy Gardiner, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Encyclopedia Americana, vol. 9, pages 322-323, copyright 1970, Americana Corporation, 575 Lexington Avenue, New York, New York, 10022, USA.

4) Robert W. Gibson, Introduction to Walter B. Gibson and The Shadow, pages ix-x, copyright 2003, McFarland & Company, Jefferson, North Carolina, USA and London, England.

5) Walter B. Gibson, Harry Houdini, The Encyclopedia Americana, vol. 14, page 455, copyright 1970, Americana Corporation, 575 Lexington Avenue, New York, New York, 10022, USA.

6) George Knowles, A Wizard of Words, Walter B. Gibson, Online Journal, copyright 2006, Controverscial.Com

7) Aleta Mayne, Behind The Shadow, Colgate Scene, Spring 2016, news.colgate.edu.

8) William V. Rauscher, Walter B. Gibson-Wizard of Words, Online Journal, copyright 2021, MysticLightPress.Com.

9) Thomas J. Shimeld, Walter B. Gibson and The Shadow, McFarland & Company, copyright 2003, Jefferson, North Carolina and London, England.

10) Anthony Tollin, The Men Who Cast The Shadow, page 127, The Shadow Magazine, vol. 41, copyright 2010, Sanctum Books, P. O. Box 761474, San Antonio, Texas, 78245-1474.

***Attention Readers:

ReplyDeleteAfter careful perusal by the author, it is noted an error was made on his part, in this text. The first Sherlock Holmes story mentioned here should read as "The Final Problem, " and not "The Final Solution, " as is printed here, for citation. Mr. DeBonis apologizes for any confusion. ***